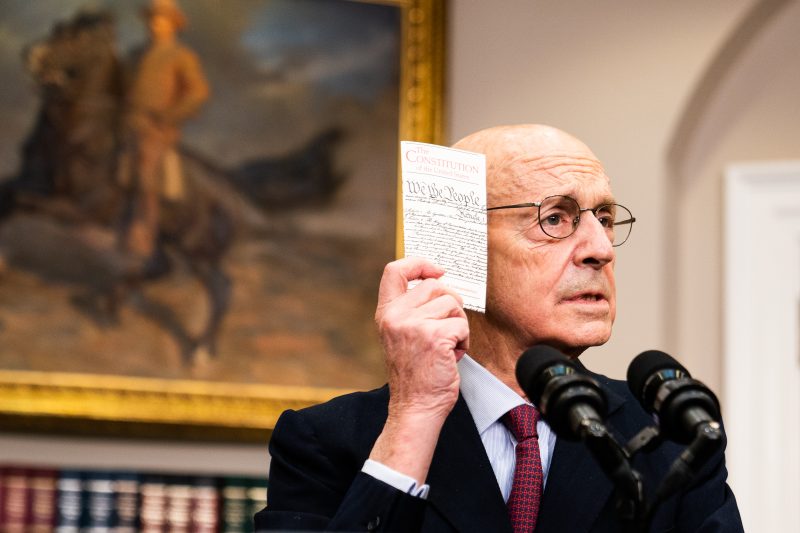

Stephen Breyer’s new book sheds light on Supreme Court cases on abortion, guns

Retired Supreme Court justice Stephen G. Breyer has never been one to shy from his criticism of textualism and originalism, the twin approaches to interpreting the Constitution strictly through the meaning of its text as it was understood at the time of writing.

During his nearly three decades on the Supreme Court, Breyer took a more pragmatic approach, issuing opinions or dissents and giving lectures that challenged originalists’ approach usually favored by conservatives. His new book, down to its title — “Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, Not Textualism” — aims to cement his belief in former chief justice John Marshall’s philosophy that “the Constitution must be a workable set of principles to be interpreted by subsequent generations.”

The book also serves as Breyer’s warning that the textualist approach by the high court’s current conservative majority has led to wrongly decided cases with significant consequences for the country — most notably the restriction of access to abortion and the expansion of gun rights.

Over more than 250 pages, Breyer breaks down what textualism and originalism are, while laying out why he believes the philosophies limit how the law is applied in the modern day. One of the basic problems with the “originalist” approach, he writes, is that it presumes judges can be historians when they have little experience “answering contested historical questions or applying those answers to resolve contemporary problems.”

“I do not say ‘never’ look to history. Often it is a useful tool,” Breyer writes. “But to tell judges they must rely exclusively upon history imposes upon them a task that they cannot accomplish.”

Alan Morrison, the associate dean for public interest and public service at George Washington University Law School, said that it should be no surprise that Breyer — who was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Bill Clinton in 1994 and retired in 2022 — would write a book raising questions about certain court decisions and expressing concern for the court’s future. In fact, Morrison noted that former justice John Paul Stevens did the same in his 2019 memoir.

“I think what Justice Breyer’s trying to do here is to lay it out in an accessible manner … to try to get people to understand why he believes that textualism is not a very good idea,” said Morrison, who noted that Breyer is a friend. “The beauty of the book is he does it with specific cases and he shows why textualism doesn’t work and why other approaches are necessary,” Morrison added.

In the book, Breyer examines in detail two major Supreme Court cases from 2022 — his last term on the bench — that he argues were wrongly decided because the majority used a textualist approach to interpret the Constitution, to the detriment of an already politically divided nation: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which ended the constitutional right to abortion that had been in place for nearly 50 years, and New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, which determined that law-abiding Americans have a right to carry a handgun outside the home for self-defense.

Breyer in his book outlines just some of the ways America has evolved since 1790: an exponentially larger population, with more citizens living in densely packed cities, coupled with guns that evolved to allow a shooter to kill more people, more quickly — “to a degree likely unimaginable to the Founders.”

“In part for these reasons, guns today pose a unique threat to American society if not properly regulated,” Breyer writes. “But originalism says that judges cannot consider these modern developments and practical realities. Nor can judges weigh the resulting interest of federal, state, and local governments in regulating guns to protect the health and welfare of all their citizens.”

In his dissent in Bruen, Breyer argued that the majority’s decision would make it more difficult for state lawmakers to take steps to limit the dangers of gun violence. The Second Amendment allows states to “take account of the serious problems posed by gun violence,” wrote Breyer, who was joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

In his book, Breyer further argues that a pragmatic approach to interpreting the Constitution as a “workable” document is required to “hold together a diverse population for hundreds of years,” citing the court’s decision in Bruen.

“How can a jurisprudential philosophy grounded in that Constitution ignore these practical realities and the deadly consequences of striking down the efforts of democratically elected bodies to address those realities?” Breyer writes. “I do not think it can.”

Breyer also goes into considerable detail criticizing the Dobbs decision, in which the court’s conservative supermajority overturned Roe v. Wade on the reasoning that those who ratified the Constitution in 1788 and the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 did not understand the document to protect reproductive rights.

However, Breyer argues, it was only White men who ratified the Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment, because at both points in time women “were not understood as full members of the political community.” (Women would not gain the right to vote until 1920.)

“The recognition of women’s rights — from the right to vote to the right to an abortion — flowed from, and contributed to, women’s ever-growing role in society, particularly in the workplace and in politics,” Breyer writes. “In the face of this progress, originalism would limit the kinds of liberty interest cognizable under the Fourteenth Amendment to those contemplated by men who existed in a time when women were not considered to have a legal identity separate from their husbands.”

Moreover, Breyer writes that a textualist approach does not necessarily bring a certainty to the law that its proponents argue it does. For instance, there remains a litany of abortion-related questions — whether the Constitution assures a woman an abortion to save her life; whether states can forbid sending abortion medication through the mail — that could lead to further Supreme Court cases.

“The Dobbs majority’s hope that legislatures and not courts will decide the abortion question will not be realized. After all, different states will enact different laws and enforce them differently,” Breyer writes. “One can — with ease — think of similar issues invoking the Second Amendment and affirmative action; those questions may also prove complex and reappear in the Court, requiring answers, which may in turn lead to further cases.”

In his book, Breyer does not directly criticize Supreme Court justices who hew to textualism and originalism, going only so far as to refer to “several new Justices [who] have spent only two or three years at the Court” who have weighed in on major cases. The three new justices to whom he is presumably referring — Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, all picked by former president Donald Trump — are mentioned only a handful of times, if at all.

“Major changes take time, and there are many years left for the newly appointed Justices to decide whether they want to build the law using only textualism and originalism or instead taking advantage of all of the methods I have described here,” Breyer writes. “But in planning how they would like to change the interpretive system, they must think about what will work best for the Court and for the country. They may well be concerned about the decline in trust in the Court — as shown by public opinion polls.”

Breyer’s book is set to be released March 26, coinciding with the date the Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments in a case that will decide whether to limit access to the medication mifepristone, which used in more than half of all abortions in the United States.

Ann E. Marimow contributed to this report.