Bill Clinton is a lion in winter addressing his 12th Democratic convention

CHICAGO — Imagine seeing Lyndon Baines Johnson, if he had still been alive more than three decades after winning his first Democratic presidential nomination, striding to the podium at the United Center in 1996 to speak at the convention that renominated Bill Clinton. That is the equivalent measure of time, 32 years, between Clinton’s first nomination and the speech he will deliver in that same Chicago arena Wednesday night on behalf of Kamala Harris.

Clinton was only 46 when he entered the White House, the third-youngest president in U.S. history, behind only Teddy Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, his boyhood hero. Now, having just turned 78 on the first day of this convention, he is the lion in winter, or at least an old cat lolling in the late summer sun.

It is tempting to say that this might be Clinton’s last hurrah, but that was said many times during his political career, and he defied the assumption every time. Loss and recovery is the theme of his life. When he was a teenager, he feared that he would die an early death like the other men in his family, but he has somehow survived beyond his own expectations. It has now been 20 years since he was first diagnosed with heart problems and underwent quadruple-bypass surgery. He has long since abandoned McDonald’s cheeseburgers to become a vegan, and has lost considerable weight, but his health has wavered over the years. He often appears frail and slightly shaky, his voice a relative whisper of the good-ole-boy twang he had as the Elvis of Arkansas. The signature lip bite is still there, as is the finger-punching style he picked up from Kennedy.

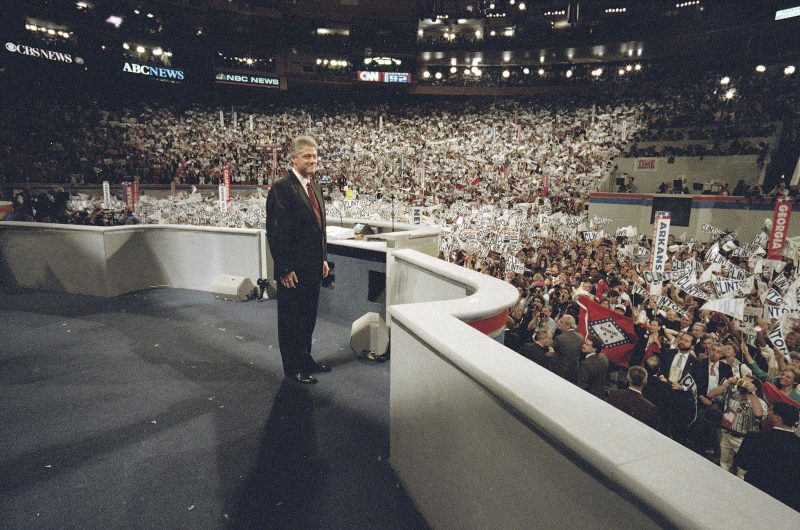

But if the man is diminished, it is not only physically. The world has changed around him. At the New York convention where he first won the nomination in 1992, the theme song was Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop (thinking about tomorrow).” This week at the United Center, yesterday’s gone and tomorrow is here, and it’s all about a youth culture of social media influencers and rappers and a joyously free-flowing aura that smothers the cultural vibes of Clinton’s once-hip baby boom generation. Clinton’s trademark phrase was opportunity and responsibility. Harris’s is freedom.

And while the Democratic Party of the 1990s largely defended Clinton and looked past the sexual misbehavior that led to his eventual impeachment by an overzealous and hypocritical Republican House, his personal actions took on a darker hue years after his presidency as the #MeToo movement exploded the careers of other powerful men who also had sexually exploited vulnerable women. Clinton now appears as a flawed but still iconic figure in the party, illustrated by the fact that Harris and her convention planners could have kept him out of a prime-time speaking slot but chose instead to shine their spotlight on him.

Clinton’s political life can be measured by political conventions — like measuring a tree’s age from rings on the trunk. His first convention speech was in 1980, when as a 33-year-old governor, he was assigned to read what amounted to a scripted eulogy to the late president Harry S. Truman. His speech Wednesday night will be his 12th, with the ups and downs of his career documented in the 10 speeches in between.

The low point was in 1988, when he delivered the keynote speech in Atlanta and the lights were not dimmed and he had to compete with the constant chatter of an audience that was not paying much attention, finally provoking someone backstage to place the words “Please finish” into the teleprompter. The loudest cheer his speech elicited was when the then-governor uttered the words, “In conclusion …” The performance was considered such a disaster that some pundits predicted a quick end to his obvious presidential ambitions, not the first time he was prematurely buried. Four years later, he was atop the ticket and headed for the White House.

The high point might have been neither of the speeches he gave at his own nominating conventions in 1992 and 1996, but rather the one he delivered in 2012 at Barack Obama’s renomination convention in Charlotte. There was no love lost between the two men; Clinton was still bitter that Obama had defeated his wife Hillary for the nomination in 2008. But after four years in office, even after he had done something the Clintons could not do when they were in power — pass a major health care act — Obama struggled to explain his policy successes. His reelection was no sure thing. Obama excelled at the uplifting rhetoric of hope, but when it came to policy, he tended to sound too professorial and subtle for a skeptical public. So up stepped Clinton, the hoarse whisperer to the middle class, plain-folksing his way through one extemporaneous riff after another to make the case for Obama with simple and powerful language in a way that Obama himself could not.

The joyful warrior attitude that Harris and her running mate, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, have exuded in the past month is something that Clinton can relate to. No one loves politics more than he does. At the final stop of his last campaign in 1996, he stayed in the hall until the last person had left, finally shaking the hand of the janitor who was there to clean up. One suspects he might want to do the same thing Wednesday night.