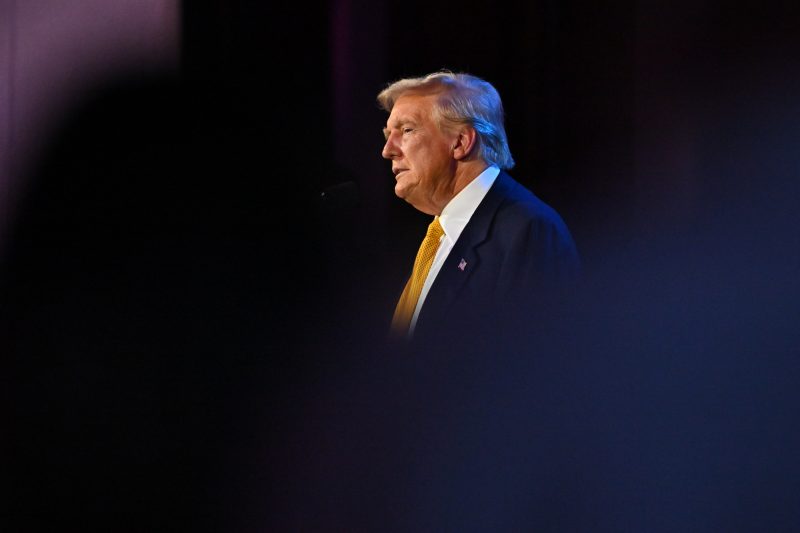

Foreign leaders seek meetings with Trump as knife-edge election nears

Foreign leaders traveling to the United States to attend the U.N. General Assembly this week in New York have also been meeting with former president Donald Trump, as they hedge their bets in case of a Trump victory in the November election.

Trump is scheduled to meet this week with the president of the United Arab Emirates, Mohamed bin Zayed al-Nahyan, and British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, according to people familiar with the discussions who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share private details. On Sunday, Trump wrote on social media that he had met with the emir and prime minister of Qatar at Mar-a-Lago, his private club and residence in Florida.

The emir, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, “is someone also who strongly wants peace in the Middle East, and all over the world,” Trump wrote. “We had a great relationship during my years in the White House, and it will be even stronger this time around!” The Qataris have played a crucial mediating role in cease-fire talks between Israel and Hamas.

The Qatari and Emirati embassies did not respond to requests for comment. Representatives for Starmer also did not respond.

The meetings reflect an acknowledgment by a wide range of foreign governments, from Europe to the Persian Gulf, that Trump may soon return to the White House and take over management of multiple global conflagrations, including Russia’s war in Ukraine, the civil war in Sudan, and Israel’s war in Gaza and its escalating conflict with Hezbollah.

Mohamed, the Emirati leader, met separately in Washington this week with President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic presidential nominee. Starmer met with Biden at the White House earlier this month. The only other foreign leader Harris is scheduled to see this week is Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, according to a person familiar with her schedule.

Zelensky said over the weekend that he intended to discuss plans for his country’s conduct of the war with Biden, congressional leaders and both presidential nominees. Trump, at a campaign rally in Georgia on Tuesday, derided the Ukrainian president as “the greatest salesman on Earth,” expressing doubt that Kyiv could fend off Russia’s advances but also boasting that he could end the conflict.

“We’re stuck in that war unless I’m president,” Trump said.

A Trump spokesman declined to comment on the meetings.

This week’s engagements are notable because they include foreign leaders beyond those known to be friendly with Trump. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, whose nationalist agenda is acclaimed by many of the former president’s supporters, visited Trump in July. Trump has also spoken to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, a relationship he cultivated while in the White House, including by making Riyadh his first foreign stop as president.

It’s not unheard of for presidential candidates to engage with representatives of foreign governments. Both Trump and Democrat Hillary Clinton met with foreign officials while campaigning for the presidency in 2016. During his bid for the White House in 2008, then-Sen. Barack Obama also met with foreign heads of state during a swing through Europe and the Middle East.

But private citizens are barred from interfering with U.S. diplomatic relationships under the Logan Act, a 1799 statute that makes it a felony to engage “with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the United States.”

Stephen I. Vladeck, a professor at the Georgetown University Law Center, said the extent of interactions between presidential candidates and foreign leaders makes clear that the Logan Act, which has barely been tested in court, is toothless. He said there are good reasons candidates would want to prepare — and why foreign heads of state would want to get to know possible incoming American leaders. But the potential for abuse is worrisome, he added.

“It shouldn’t be controversial that people who are outside of the administration should be limited in their ability to influence or undermine the administration’s foreign policy,” Vladeck said. “Someone running for office might make some sort of backroom deal: ‘If you do something or don’t do something until I’m elected, I promise to help you if I win.’ That should bother any American.”