The racism and ahistoricism of Trump’s ‘poison the blood’ rhetoric

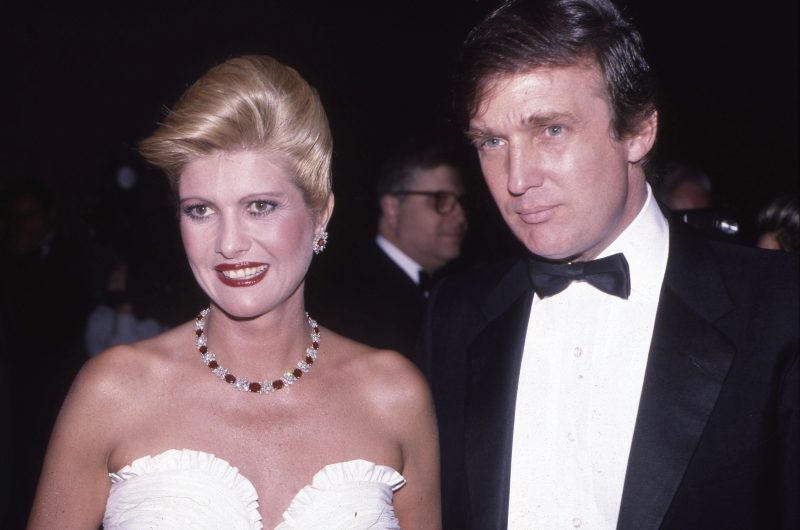

Donald Trump doesn’t hate immigrants. He married two women who immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe. Nor is he particularly insistent about immigrants having children in the United States. His three oldest children were born to Ivana Trump, who at the time had not yet become a citizen. His youngest child was born in March of the year that Melania Trump got her citizenship.

So when Trump talks about how immigrants are “poisoning the blood” of the country, as he did over the weekend, we don’t need to pretend that he is offering a sober observation about shifts in the country’s population. He is, instead, making a demagogic appeal to Americans who — like so many Americans before them — view newcomers with fear or anger.

Despite their almost uniformly being descendants of immigrants themselves.

The country is experiencing unusually high levels of immigration, which exacerbates those fears (and increases Trump’s ability to leverage them for political purposes). These figures are often misinterpreted, it’s worth noting, with only a percentage of those stopped at the border (many of whom are seeking asylum) being released until legal hearings that will determine if they are granted the right to remain in the country. Many of those apprehended are deported; this was particularly true under the pandemic-triggered policy that allowed law enforcement to deport immigrants quickly. (Many tried to reenter soon after, driving up the number of apprehensions.)

The country in recent years, though, has not experienced unusually high levels of immigrants — that is, foreign-born residents of the United States. Historical comparisons are tricky, given the spottiness of records over the country’s history. But it seems safe to say (using separate historical assessments compiled by Pew Research Center and the Migration Policy Institute) that the percentage of the population that was born outside the United States has increased since immigration laws were loosened in the late 1960s but are not at the highs seen a century ago.

The assessment offered by Pew suggests that more than one-fifth of the country was born outside the United States 100 years ago. According to 2023 numbers from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey even adding 10 million immigrants to the population wouldn’t result in 20 percent of the population being born outside the country.

A central difference, of course, is the places of origin for those immigrants. Until immigration laws were loosened in the 1960s, the vast majority of immigrants to the United States came from Europe. In recent decades, they have come from Latin America (particularly Mexico) and Asia. Immigration from Europe is relatively low.

But, 100 years ago, that did not mean that immigrants from Europe were welcome. There was a huge backlash against immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe in particular; the arrival of large numbers of Italians triggered anti-Catholic rhetoric and even violence. (You could have asked Tucker Carlson’s ancestors about that.)

Race is intertwined here. Those new arrivals a century ago weren’t seen as non-White, exactly, but were seen as “racially inferior,” as researchers Cybelle Fox and Thomas Guglielmo wrote in 2012 — unclean, dangerous. Those Eastern European immigrants were often seen as physically distinct from “White” Americans in a similar way to how Hispanic and Asian immigrants are viewed as distinct today.

Trump is typically unsubtle about this. In 2018, The Washington Post reported on his disparaging of immigrants from Africa and other places with large non-White populations as unwelcome, and he lamented that more people weren’t coming from northern Europe.

The most obvious and immediate response to the idea that immigrants are “poisoning the blood” of the country is to point out that the United States is inextricably constituted of immigrants and their children. We don’t live in Finland; we live in a country where the only native resident population is Native Americans and no other family can claim to have been here longer than about 400 years. Trump’s rhetoric is a bit like complaining about someone pouring tap water into the pond behind a dam.

It’s particularly hollow given how immigrants are underrepresented in positions of power. In Congress, for example, only about 3 percent of members were born outside the United States, according to Pew, compared with 16 percent of the population. Only about 15 percent of the members of Congress are immigrants or children of immigrants, about half the rate of the population overall.

A 2017 report looking at the effects of immigrants on the economy nonetheless found that the country is increasingly dependent on immigrants and the children of immigrants to fill jobs. The chart below, from my book about generational change in the country, shows how the share of workers who are third-generation Americans or higher has plunged since the baby boom. Increases in the workforce come from immigrants and their children.

The American population is growing because of immigration. It’s a signal advantage we enjoy, the reason that our population — unlike, say, China’s — isn’t contracting, exacerbating economic problems.

This article has extrapolated a lot of information about immigration from Trump’s comments when, again, his intent is less complicated. He’s simply amplifying his base’s fears of the perceived decline of traditional White Christian America. That he is the child and the grandchild of immigrants, married two immigrant women, and has four kids with immigrant parents — a by-no-means-uncommon situation — is simply waved away.

It’s useful to remember, though: Had he married a Catholic from Eastern Europe a century ago, he might have been the target of similar demagoguery.